Una cubana negra en labana. A Black woman in Cuba.

I was born in Havana on a mildly chilly morning. From what I know, the typical Cuban breeze was mostly idle. My mom was 25 and my father 27 — young for today’s standards. But they were married and I was their second offspring, 9 years apart.

We emigrated out of the destitute isla in pursuit of freedom. We lived in Miami at the height of the influx of Cubans arriving by rafts and other risky and wildly unfathomable means of transport: a makeshift raft designed with tractor trailer wheels, a motorcycle motor, and wood planks comes to mind. At the time, the coveted American city was replete with pride and accelerated anxiety to make a new life; to leave behind the horror Castro had falsely established on the platform on which he successfully ran. By all counts, Miami was the free Havana where cubanos could enjoy their culture, speak their language, go to the grocery store and shop in abundance, have running water (and toilet paper), and not wonder when the next apagon (island-wide electrical shutdown) would happen.

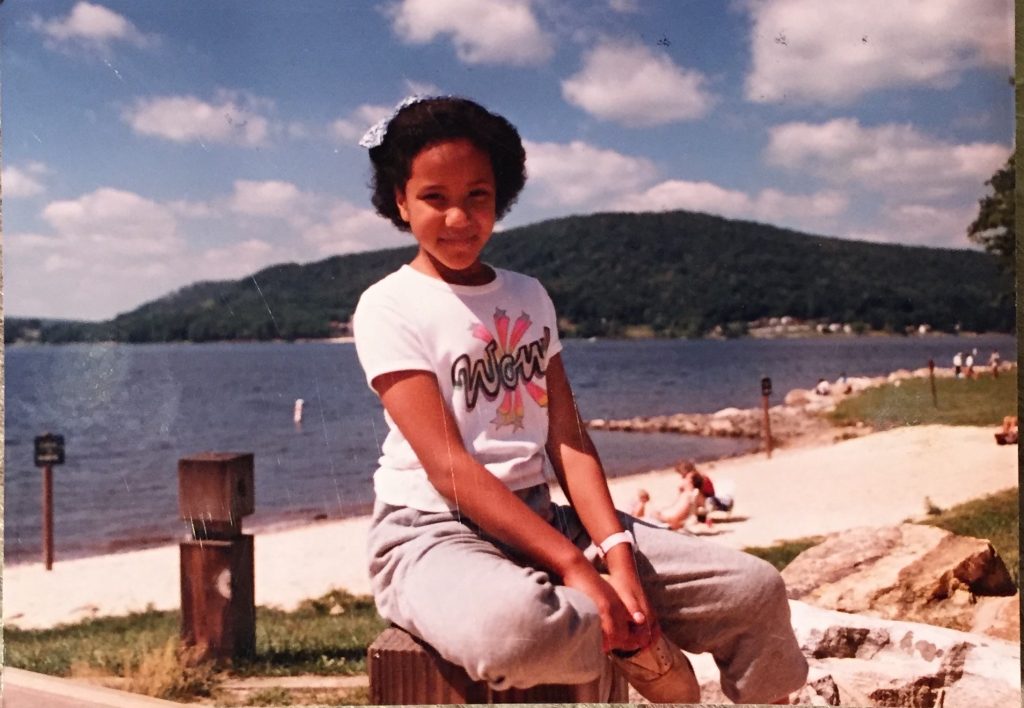

We left Miami for D.C. to enjoy a more “American” culture when I was barely 6, having just learned how to speak English the previous year. I was young. A child. Until then I was just that — a child my parents loved and exposed my 3 siblings to this life vastly different from what they knew.

And just that quickly, I was more than just a child. I was a brown child that looked and spoke differently from the other children. We were the only non-white kids in a 3-block radius. In contrast to our diverse community in Miami, we stood out. My father is darkest in the family, having had really kinky hair up until his early 60s. My mother has strong Chinese genes and is fair-skinned with dark black hair. My nose is far from a European or even Central or South American aesthetic.

Dad, Mami, Sis, and eldest Brother, circa 1983/84 in Miami

Within a year of settling into this new all-American life, a white boy, whom I considered my friend, called me “brownie girl”. Though we played almost daily, he felt incredibly comfortable referring to me by other than my name. What stands out still is that his tone was not a jestful one in attempt to parallel me to a perfectly warm kids’ treat. He was mocking me and trying to ruffly my feathers. I was 7 at the time and didn’t quite get it but I knew something wasn’t right. His connotation was intentionally bigoted.

My fluency in Spanish wasn’t considered cool or “sexy.” It was a simple reminder that I was different. I ended up in a high school that boasted at the time a graduating class made up of 52 nationalities. You’d think our exposure to so many cultures in one building fostered open-mindedness and an understood blindness to color, but in truth, turned out to be a fostering tool to further develop those stereotypes. A Black female friend told me once in 10th grade if her kids ever dated a Hispanic, she’d disown them. She now has 12 and 14 year old daughters. I wonder how her feelings have changed. Ironically, she remains to be one of my closest friends.

While I spoke Spanish at home, ate and cooked our native food (a combination of African and Spanish) and watched all the dramatic novelas with Mami, my experiences at school were different. I personally identified with the Black crowd. We dressed differently. We had different jokes. We had different hairstyles. We had different slang. I was friends with and only attracted to the Black boys. Truthfully, the white boys weren’t ever interested. And the one time I was attracted to a white boy, he humiliated in public by telling me he didn’t like me back. That was in 3rd grade. But was it because I was a little Spanish-speaking Black girl?

I was too Black for the Latinos. But that affinity and identification to Black people led to ostracization by a lot of the Black girls. My light skin didn’t render me Black enough and so I was a “wannabe” to them.

Admittedly, I suffered through an identification crisis sometime during those 4 years. Ironically, most of my white friends, barring the kid down the street and a few other mean girls, didn’t seem to care what my ethnicity represented. A few white girls, however felt the same as the Black girls and thought I was a wannabe. But mostly, I was just a long-legged, lanky girl. My Latin friends, all 3 of them, and I didn’t have anything in common other than our language our dinner hour.

Those were my high school years.

While I happily came to terms with being a Black cubana, culturally rooted in Jamaican and Afro-centric traditions – our song and dance, our soulful food, etc… — it’s not been so easily accepted by my peers today. The wonder of my ethnicity and race is even more mystifying to an even larger group of people. White people have minimally weighed in and wonderfully don’t seem to care; at least not blatantly. Though an incident I personally encountered at UVA loosely represented the separatist culture on campus. However, and quite disturbing, has been the dissenting opinion I’ve received from some Latinos, namely Mexicans. Questioning my Blackness and my identification as such, no matter my late Jamaican paternal grandfather, has caused real riffs. I don’t have an accent. I wasn’t raised in Cuba. How Latina am I then?

But the most baffling sentiments and questions have come from Black people (non-Latin). I was once asked to leave an event in Atlanta which was created by and hosted exclusively for Black independent business owners. Yes, this really happened. It was a prejudice moment where my Blackness wasn’t immediately noticeable and therefore didn’t qualify me as a befitting attendee. I wasn’t wearing Kente prints as many of the other event-goers were and my hair was tucked underneath a hat in contrast to cultural hairstyles (locks, cornrows, twists, etc.). I considered the environment and realized the limited mentality was more toxic to them than they could even see.

But even some of my closest friends have alluded to me not being a “real Black person,” referencing my “good hair” or light(er) skin. A boyfriend’s (from my early 20s) mother disapproved of me because our “relationship mirrored that of Jennifer Lopez and Sean Combs” at the time. She went on to imply I’d not be a proper support system to his two young boys because I was culturally unaware, aka, not Black enough. That same guy (lighter than I with green eyes) once suggested I would be a typical Latina stereotype.

The unapologetic jokes continue and I gracefully laugh my way into beneficial situations where my ethnicity and bilingualism is celebrated.

But in all of my sympathetic glory of being a solid Black woman who happens to articulately speak Spanish, the lines drawn in attempt to pigeon-hole me into one class or another is simply ignorant. The African ancestry in my native island is just as strong if not more closely tied to the origins of Blackness than here in the U.S. However, my own Cuban people are arguably the first to call out Black people. The lighter you are in that nation, the more attractive you’re considered. A darker Black Cuban is treated with less dignity, I’ve eye-witnessed. There’s a present but unspoken deniability about our own.

Ultimately, the irony all lies in the aesthetics of a Black person. By first impressions, some of my facial features are more “Blackish” than a lot of my Black American friends, namely my nose. My natural curly hair is thick and full, more than most of my Latina-ish sisters. But we — Black, White, Latino, etc… — overlook that. There is no true reconciliation with my look and my race. At that same event in Atlanta, I note a very light skinned woman with much narrower features and similar textured hair, was allowed in without incident. The dangerous error made in our society today is to typify any one person or ethnic group. We are not monolithic.

{Read about being called a Ni88er Woman here and here}

Black is an American construct. The classification makes it facile for society to use a catchall word to describe anyone of the African Diaspora. Ideally, yes, our country of origin wouldn’t necessarily preclude us from acknowledging and loving our racial culture. Alas, we’re in a society where being Black is still equated with subpar existence and capability.

Black is a culture. It’s a thought process. It’s American history. It’s beautiful. It’s proud. It’s a sensitive connection to disparity. Sometimes it’s not just black or white. My Cubanism doesn’t make me any less Black than my fellow Cuban actor, Laz Alonzo, whom to my knowledge, is roundly considered a Black man. And I’m sure we both love our respective rumba, Celia Cruz, and platano frito as much as we love our Marvin Gaye or the Electric Slide.

My family celebrated our 30-something anniversary of arriving in the U.S. just last week. I’m as American as it gets. I’m as Cuban as they come. I’m as Black as I want to be. It’s my hope people see me for a thick curly-headed educated woman with strong convictions and heartful giving who speaks several languages.

I’m Cuban and I’m proud. I’m Black and I’m proud.

Next, I’ll discuss the issues associated with our curly hair for both Black and Latin women.

Eat well, love unapologetically, pray with true intention, and take care of yourself.

78 thoughts on “On Being Black: A Look at my Afro-Cubanness”

Loved reading this cuz!

I am just coming across your blog . My family is Afro-Cuban and we have lived most of what you spoke on. We all look African American and identify as black. We embrace our Afro Cuban heritage that originates in Santiago Del Cuba. I truly appreciate your blogs in so many ways. As a woman. As an AfroLatina. As a black woman in America. As a foodie. 🙂 Keep blogging sis.

Hi, Jordan.

I’m sorry I’m just seeing your comment! I don’t know enough of us so I’m glad you found my site! I definitely ID as Black, also, though I get a lot of questions from my non-Latino Black friends. It’s still interesting to me. This topic is so rich so I hope to keep having it. Thanks for listening. I hope you’ll come back! Happy Hispanic Heritage Month.

20739 203703There is noticeably lots of dollars to comprehend about this. I assume youve made certain good points in capabilities also. 317136

tadalafil: http://tadalafilonline20.com/ tadalafil 30 mg

tadalafil 30 mg tadalafil daily use

generic tadalafil united states

medications without a doctor’s prescription buying prescription drugs from canada

generic pills for ed prescription drugs without a doctor

967650 537285Fairly uncommon. Is likely to appreciate it for men and women who contain community forums or anything, internet web site theme . a tones way for the client to communicate. Outstanding job.. 930107

pills without a doctor prescription medications without a doctor’s prescription

medications without a doctor’s prescription: https://genericwdp.com/ trusted india online pharmacies

india pharmacy mail order: https://genericwdp.com/ generic pills for sale

prescription drugs online without doctor buy prescription drugs online without

buy real viagra online best place to buy viagra online

best place to buy generic viagra online

viagra price buying viagra online

buy viagra online canada

price of viagra mexican viagra

generic viagra walmart

viagra 100mg price viagra amazon

buy real viagra online

online doctor prescription for viagra best place to buy generic viagra online

where can i buy viagra over the counter

cheap viagra online online doctor prescription for viagra

viagra cost per pill

п»їviagra pills when will viagra be generic

viagra without a doctor prescription usa

cost of viagra online doctor prescription for viagra

how much is viagra

how much is viagra price of viagra

viagra over the counter walmart

online doctor prescription for viagra viagra cost per pill

viagra over the counter walmart

best over the counter viagra mexican viagra

viagra over the counter walmart

viagra from india cost of viagra

viagra online usa

paxil 5 mg generic paxil

soma therapy ed

where to buy chloroquine chloroquine tablets buy

zithromax buy online no prescription where can you buy zithromax

cheap drugs online

where can i get zithromax where can you buy zithromax

buy viagra online usa https://viagrapills100.com/ viagra amazon

viagra amazon https://viagrapills100.com/ cost of viagra

best over the counter viagra https://viagrapills100.com/ viagra cost

buy viagra online canada https://viagrapills100.com/ viagra from canada

where to buy viagra online https://viagrapills100.com/ buying viagra online

buy viagra online canada https://viagrapills100.com/ where to buy viagra online

buy generic 100mg viagra online mexican viagra

over the counter viagra

ed remedies that really work drug store online

diabetes and ed

cheap ed pills from india cheap ed pills in mexico

cheap ed pills in mexico

ed pills without a doctor prescription amoxicillin without a doctor’s prescription

ed pills online

buy ed pills from canada cheap ed pills from canada

cheap ed pills usa

buy ed pills ed pills without a doctor prescription

ed pills without a doctor prescription

cheap ed pills from canada buy ed pills

buy ed drugs

cheap ed pills from canada cheap ed pills in mexico

buy ed pills

https://gabapentinst.com/# neurontin generic brand

neurontin capsule 600mg: cheap neurontin – generic neurontin 300 mg

http://hydroxychloroquinest.com/# hydroxychloroquine cost

neurontin prices generic: cheap neurontin – buy generic neurontin online

https://hydroxychloroquinest.com/# plaquenil brand name

generic hydroxychloroquine: cheapest plaquenil – hydroxychloroquine 2

http://zithromaxproff.com/# how to buy zithromax online

zithromax for sale online

https://zithromaxproff.com/# zithromax 500mg over the counter

zithromax antibiotic

http://zithromaxproff.com/# zithromax 500mg price

zithromax capsules

http://zithromaxproff.com/# where can i buy zithromax in canada

zithromax canadian pharmacy

http://zithromaxproff.com/# zithromax for sale 500 mg

zithromax 500 mg

buy erythromycin generic: buy tinidazole generic

generic trimox

tetracycline online: vantin tablets

terramycin for sale

generic fucidin: ceftin tablets

omnicef online

buy augmentin: buy zyvox

fucidin capsules

штабелер электрический самоходный

https://www.shtabeler-elektricheskiy-samokhodnyy.ru

подъемник ножничный передвижной

https://nozhnichnyye-podyemniki-dlya-sklada.ru

электророхли

https://samokhodnyye-elektricheskiye-telezhki.ru

подъемник мачтовый

https://podyemniki-machtovyye-teleskopicheskiye.ru

телескопический подъемник

https://podyemniki-machtovyye-teleskopicheskiye.ru

гидравлический стол

https://gidravlicheskiye-podyemnyye-stoly.ru

The writing style in this article is captivating and engaging. The author has a real talent for storytelling and making complex ideas accessible to a wide audience.

https://www.govtjob.me/grace-charis-height-age-net-worth-real-name-career-boyfriend-parents-biography-grace-charis-wikipedia/

Системно-семейные расстановки по Хеллингеру. https://rasstanovkiural.ru

We recommend exploring the best quotes collections: Self-Love Quotes From Great People

devido a esta maravilhosa leitura!!! O que é que eu acho?

pokračovat v tom, abyste vedli ostatní.|Byl jsem velmi šťastný, že jsem objevil tuto webovou stránku. Musím vám poděkovat za váš čas

) Znovu ho navštívím, protože jsem si ho poznamenal. Peníze a svoboda je nejlepší způsob, jak se změnit, ať jste bohatí a

) Jeg vil besøge igen, da jeg har bogmærket det. Penge og frihed er den bedste måde at ændre sig på, må du være rig og

že spousta z něj se objevuje na internetu bez mého souhlasu.

det. Denne side har bestemt alle de oplysninger, jeg ønskede om dette emne, og vidste ikke, hvem jeg skulle spørge. Dette er min 1. kommentar her, så jeg ville bare give en hurtig

e dizer que gosto muito de ler os vossos blogues.

الاستمرار في توجيه الآخرين.|Ahoj, věřím, že je to vynikající blog. Narazil jsem na něj;

také jsem si vás poznamenal, abych se podíval na nové věci na vašem blogu.|Hej! Vadilo by vám, kdybych sdílel váš blog s mým facebookem.

Рекомендую – какие бывают скороварки

https://shvejnye.ru/